Odilim Enwegbara

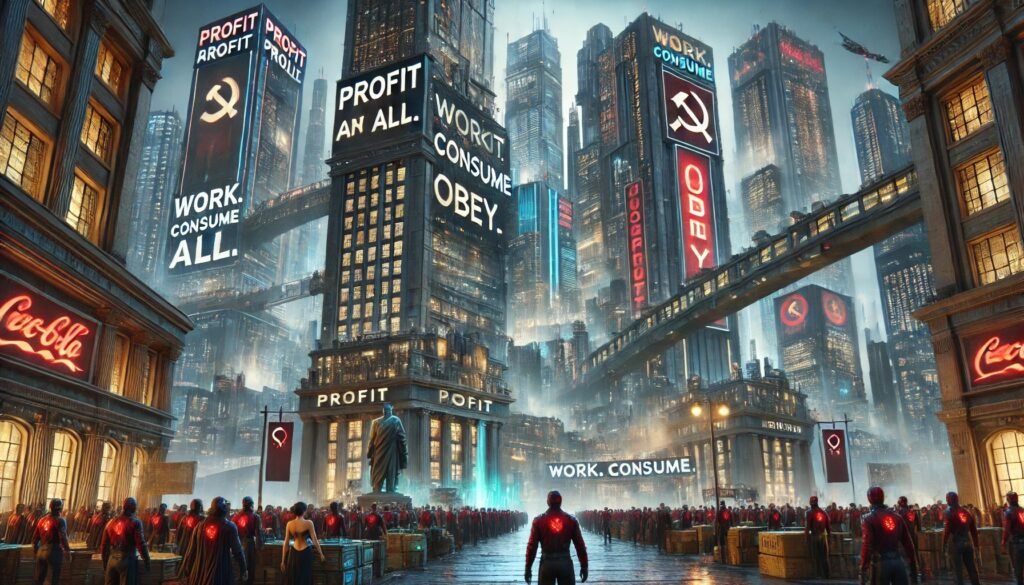

Driven by moral outrage over the unchecked human selfishness embedded in capitalism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels crafted The Communist Manifesto in 1848, proposing an alternative system to mitigate capitalism’s inherent dangers to humanity.

For Charles Dickens, the grim realities of London between 1835 and 1870 reflected more than just economic dislocation—they embodied an existential struggle between two aspects of human nature: the relentless pursuit of self-interest versus the moral and intellectual revulsion at its consequences.

By 1917, this ideological struggle erupted into revolution, as the Bolsheviks overthrew Russia’s provisional government, establishing the first communist state. The global confrontation between capitalism and communism that followed—lasting from 1917 to 1991—was not merely about economic models but a deeper contest over the true nature of human motivation and social organization.

Despite capitalism’s history of instability, its propensity to exacerbate inequality, and its vulnerability to crises, it ultimately outlasted its rival. This survival was not by accident; capitalism adapted, embracing social welfare principles that softened its harsher edges. By incorporating safety nets—unemployment benefits, labor protections, and public services—capitalism absorbed the very social guarantees that communism promised, all while preserving individual freedoms. This strategic evolution strengthened its appeal, leading to the Soviet Union’s collapse and the global retreat of communist ideology.

Yet, with the fall of communism came the erosion of capitalism’s social conscience. The constraints that once tempered capitalist excesses—shaped by leaders like Bismarck, Churchill, and Roosevelt—began to unravel. The resurgence of corporate greed and deregulation has gradually stripped capitalism of its 20th-century reforms, ushering in a return to its raw, exploitative 19th-century form.

Today, multinational corporations, unbound by social contracts, seek out the lowest labor costs and the least restrictive regulations in countries like China, India, and Mexico. Governments in these regions, eager to attract investment, often offer corporations near-total freedom—sacrificing labor rights, environmental protections, and tax revenues in the process.

This raises critical concerns: Without fair wages, how can developing nations build sustainable middle-class economies essential for long-term growth? How can governments fund the infrastructure and social programs necessary to maintain economic stability when corporations contribute little in taxes? If neither workers nor governments benefit from globalization, what incentive remains to defend the current capitalist order?

As economist Lester Thurow argues in Fortune Favors the Bold, capitalism today requires another structural overhaul—one that reins in corporate excess and prevents multinational corporations from overpowering nation-states. The economic priorities of governments must be redefined to ensure a fair balance between corporate interests and the well-being of their citizens.

Without such reform, the consequences are inevitable: a shrinking middle class in the West, rising poverty in developing economies, and growing discontent that could fuel a global backlash—perhaps even a resurgence of communist movements in the very nations left to bear the brunt of unchecked capitalist globalization.